|

| ||||

|

As we descended into the valley, I was aware of a singular quality of light that seemed to emanate, almost chartreuse, from the patterned fields and terraces, and copper, from the adobe homes emerging geometric from dark, rich soil. |

|||

Most of us left the United States late on December 12, arriving in Lima on December 13, then flying to Cusco. There, eleven of us, plus drivers and (most of) our luggage, were crammed into three taxis for the hour-long drive from the Cusco airport to our hotel in the village of Yucay. I was there because of a chance phrase in a casual email from someone I had not seen in fourteen years. She was going to Peru. I had long wanted to go to Peru. So there I was. Most of the group, ranging in age from 33 to 77, was there through similar happenstance. Some of them knew the tour leaders through their healing working. Others were their friends. Others, like me, just lucked out. |

|

The Yucay hotel was a surprise. Quite beautiful, with magnificent gardens and spacious, comfortable rooms with windows that looked out on an open meadow, part of a wide valley cupped by mountains ranging from 10,000 to more than 20,000 feet. |

||

|

Our whole three-week stay was a lesson in duality. Wonders seemed perpetually countered by problems that were in turn countered by more wonders. My suitcase didn’t arrive in Lima when I did, but somehow managed to show up in my Yucay hotel room the second day I was there. A bad knee prevented some activity and a typical tourist complaint confined me to the bathroom for several days. But it all balanced. And when one roommate didn’t work out, another was just fine. Over all, we were a remarkably compatible group, sharing awe in the sights and delight in the shopping. Our first three full days in Peru were spent in Yucay and neighboring Urubama. We learned that all villages have guardian spirits, called apu, that usually reside in adjacent snowcapped mountains. These we honored in ceremony. We walked and meditated among local Incan ruins and temples and on terraces still used for farming. We wondered at the Urubamba market that, every day, spills out a cornucopia of produce and commodities. |

|

|

And we met Alfredo. He showed up with his little dog Delilah while we were having lunch in Urubamba. A friend of Viviana’s, he adopted the whole group, recommending a new restaurant for dinner that evening and, later, enlisting us as hosts to a traditional cocoa party and, still later, as guests on New Year’s Eve. |

|

The second-floor restaurant was top-notch. Chef Ricardo personally prepared salads with incredible Peruvian avocadoes and delectable main dish concoctions of meat and vegetables. Everything local, fresh and perfect, accompanied by fine wines and/or pisco sours. When all had been fed, he turned his satellite receiver to some vintage music and, with his staff, joined in a dancing celebration of a great day. |

|

|

On our fourth day in Peru, we boarded a van at 7 a.m. for the ride to Ollantaytambo where we would catch the train to Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of Machu Picchu. The Ollantaytambo station was crowded with vendors, who persisted even after we boarded, managing to sell Avishai a weaving through the window just before train started moving. |

| The train arrived on time, our reserved seats were comfortable and the ride -- up into the mountains with fern-packed rainforest on one side and churning rapids on the other -- utterly spectacular. To get from the train to the town of Aguas Calientes, all travelers must pass through a maze of vendor booths, a veritable gauntlet. Emerging, they see the river and another train track along which are squeezed hotels, restaurants, more shops, and one bank and ATM. There was always a line at the ATM. We walked along the tracks to our hotel and then to lunch. While we waited for our orders, we were serenaded by Andean musicians, one of whom played a strangely curved didgeridoo. Predictably, they sold their CDs and, predictably I bought one. Then Mario showed up, offering shoe shines. His English was excellent and his attitude, terrific. He told us he was a ‘professional’ from Lima, using his summer vacation to earn money for school. |

|

|

Wandering the non-town, I realized that I was hearing Beatles songs. Every restaurant not broadcasting canned Andean music, played the vintage group. They were so prevalent that I almost grew to hate “Hey Jude.” Later, while others soaked in the local hot springs, I had a great massage from a young woman who spoke no English. |

||

|

The next day was to be our day at the place everyone wants to see: Machu Picchu. As instructed by our guide, Alexandro, we had breakfast at 5:30 a.m., boarded a bus at 6 and were at the entrance to Machu Picchu by 6:30. During the half hour vertical ride, we rode in and out of clouds, catching fleeting glimpses of mountains and jungle. |

|

|

|

San Pedro is a cactus that can be used to create a mild hallucinogen. The peel is boiled for at least four hours to create a pale green liquid. Evidently many Peruvians drink it for meditation and ritual. When we were offered a chance to try, every one of us accepted. Viviana, Juan and Gabriel abstained so they could watch over us. We gathered in the hotel meeting room, where Gabriel smudged us with the smoke of an aromatic wood. The jar of San Pedro juice was passed and we each drank a generous and not too unpalatable portion. We then walked about a mile from the hotel to a secluded glen on the edge of field of corn. The walk was hard but I had help, especially from Juan. When I got to the glen, I lay flat on the damp ground, aware of earth energy. I could see the sparkle of air particles, the pulsing mountains, the vibrating green of the plant life. Gabriel retrieved his guitar then sang some of the beautiful songs he had composed. Most of the others sang along and danced. I stayed mostly on the side, observing. It was a joy to see Juan’s joy in his son. A gentle rain fell, adding patterns on nearby waters … and cold. |

As Juan escorted me back over the difficult path, we had an incredible, not quite bi-lingual conversation, about the tranquility of the valley and the persistence of the life force, as seen in the eucalyptus that lined the path. Young shoots grew out of the trunks of their decapitated elders, which served as their new soil. Through the barrier of partial languages we agreed: life begets life and nourishes life and returns to life and it is all a miracle and it does not end. He called it ‘returno.’ |

|

|

On the plateau below the terraces were temples to water, stones for sacrifices, the faces of first ancestors and images of sacred animals. On the condor mountain, and across the valley, were platforms for priests to meditate. The thousand-acre complex is itself in the shape of the Tree of Life and the first houses clustered like a cob of corn. All of it comprised an astronomy center for the early empire. Everywhere, remnants of ritual and worship, surrounded by the spirits of the mountains. |

Unlike Machu Picchu, Ollantaytambo is a living city. You can walk Incan streets, still bisected with water channels, and enter domestic courtyards, where people live, raise guinea pigs for food (I did not eat any) and sell handicrafts to tourists. Including me. |

|

|

During the Christmas season, most Peruvian hotels, churches, and schools hold cocoa parties for children in their vicinity. Our Yucay hotel had one and Alfredo traditionally hosted one for his Urubamba neighborhood. Using one of his three cell phones, he negotiated a deal with Viviana: he would supply the traditional cocoa and cake that our group could serve when we distributed the traditional trinkets, which we would provide. In return, he would fix us dinner in his incredible house. He expected between 75 and 100 kids to show up. We agreed to the event that would occur on Friday, Dec. 21. Late that morning we climbed into the van and disembarked into Urubamba’s plaza. While Viviana and Avishai procured the trinkets, the rest of us wandered the town. I settled in the plaza where I made mime-friends with two little girls and, with the mime-permission of their father, bought them ice cream … which completely ruined their previously spotless outfits. |

Trinkets in hand, we crowded back into the van and rode up the mountain to Alfredo’s establishment. There we wrapped 100 little packages, struggling with tape that didn’t stick too well as we molded sparkled dark green paper around little toys. Finally, we moved to the hotel courtyard to greet the hordes of kids waiting outside the gate. We organized them into circles. I got all boys, including Carlos. He had a piece of plastic string which he tore into strands, which I in turn tied together into a sort of flower which I hung on a little bush, much to his delight. Others in our group organized real games, which the kids didn’t really understand but seemed to enjoy anyway. They consumed gallons of cocoa and their huge chunks of cake and left exultant with their trinkets. |

|

|

We stopped at Maras, where the Incan system of more than 5,000 drying pools is still used to evaporate water from salt springs and the salt collected for distribution – mostly by burros. We then went to Moray, a vast complex of concentric terraces that served the Incas as an agricultural laboratory. They planted various crops, brought from all over the Inca kingdom, to determine which were best suited to which environment. Here it was easy to believe that the Incas domesticated more than 500 kinds of plants. |

As we drove toward our next destination, Leon looked up at the mountains and worried aloud at the diminished snowcaps. When those glaciers are gone, he said, it will be the end of Peru [which depends almost entirely on snow melt for its water]. Not always glum, he noticed my frequent pit stops and told Viviana that Peruvians didn’t get diarrhea because they had the stomachs of pigs. |

|

|

By this time, I was beginning to see things less as a dazzled tourist and more as a careful observer. Living in an adobe house with a dirt floor and minimal plumbing was neither romantic nor particularly sanitary. Life in the valley was tranquil but also hard. Even the Martinez family complex, although large and rambling and full of charm, was hardly luxurious. It would not have done well on the U.S. real estate market. As simple, and somehow honest, as the little villages were, I was amused at the occasional and completely incongruous gas stations. Scattered sparsely and essential, there seemed no rationale for the pinup posters each station used to lure vehicles to the pumps. |

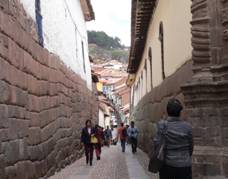

On Dec. 26, the group traveled back to Cusco to settle in Norma’s hostel for several days’ exploration of the ancient city, once the Incan capital and thus the navel of the world. Still infirm, I obtained some antibiotics and felt better almost immediately. |

|

|

I was able to walk to the Plaza de Armas and up and down the cobbled streets amid Cusco’s magical blend of Incan and Spanish colonial architecture. We invaded a little shop and some of the group danced with the owner while others insured her day’s profit. That night, the group enjoyed an evening performance of Andean folk dances. The music and dances were all pretty similar but the succession of costumes was stunning. Woven in intricate and colorful patterns and, literally, capped with headgear distinct for each village, they whirled and stomped across the stage with the exuberance of a present rooted in long tradition. |

Viviana’s good friend Eliana joined the group after flying in from Lima. Dedicated to helping the people of her country, she works as a sociologist for international agencies such as Save the Children and UNICEF. She added great dimension, depth, to our tour. |

|

|

After lunch with Eliana and others, I wandered off on my own. At the doorway to a small courtyard, a beautiful woman who said her name was Frances invited me into her shop, hung with hand-woven ponchos. One combined shades of scarlet with black and golden accents. It now hangs in my closet. |

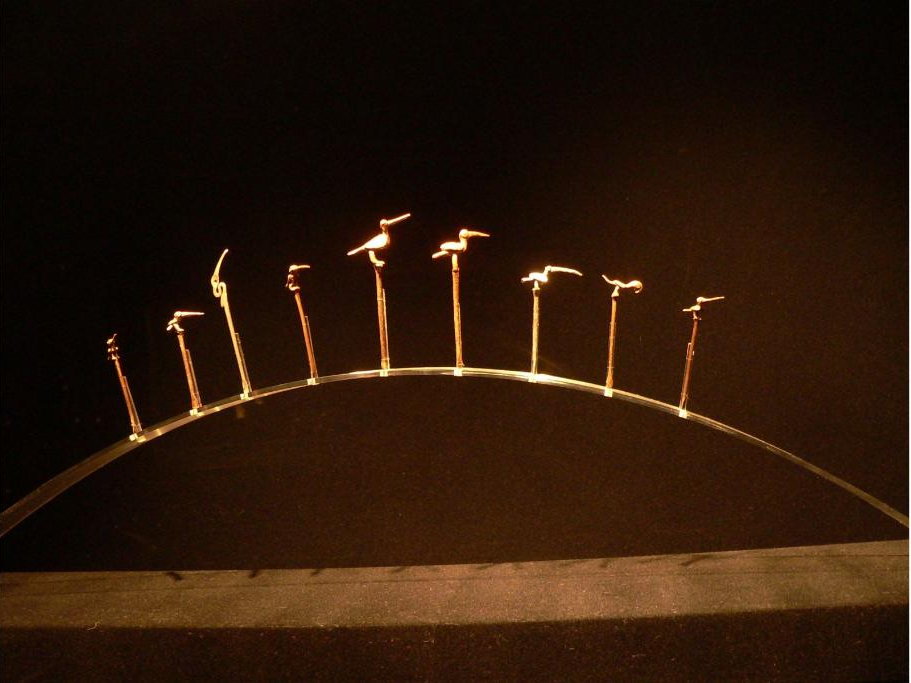

On my way back to the hotel, I took the tour of the Temple del Sol. Actually, it is a complex of temples – for rainbows, thunder and water, all interconnected, and the sun and moon. There was also an observatory and, on the front terraces there were once golden images of animals and plants. On the 28th of December it was home to a nativity scene, complete with a giant llama. All the temples had been covered with gold and their niches filled with golden images. The gold was stripped and melted down by the Spanish, who built a cathedral over everything. The ruins were hidden until a 1950 earthquake destroyed much of the cathedral. The Incan structures survived because their masonry is astounding. Stones, often trapezoid in shape, are fitted together in sort of a tongue and groove fashion, so precisely, without any mortar, that you cannot insert a knife blade in between the blocks. So they stand while the Spanish buildings crumble and the heritage, hidden for 400 years, is again a Cusco glory. |

|

|

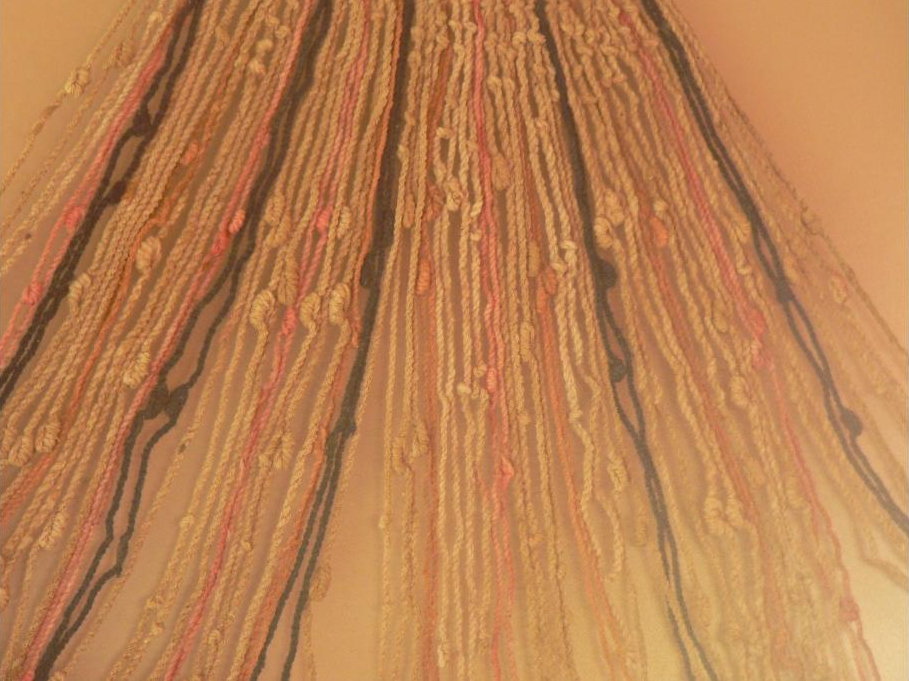

That evening Viviana’s uncle, Mario, a distinguished anthropologist, Gabriel and Eliana joined us for a Shabbat followed by a sort of salon. Norma, quite awed to have him in her home, pulled a chair into the crowded living room to hear Mario talk about the still-underestimated depth of the Andean heritage. He talked about the quipu, bundles of colored string knotted at varying intervals that were used by the Inca for inventories and, perhaps, as a way to record laws and legends. Had more of them survived, anthropologists would have a better chance of deciphering their obviously sophisticated code. He said there had been a huge storehouse of quipu in Cusco that the Spanish burned to the ground. Like, I thought, burning the library at Alexandria. |

Norma’s hostel had its drawbacks. The rooms were not heated and, according to my little travel clock thermometer, the temperatures hovered between 54 and 60. But it was full of fascinating things and conversations. |

|

|

But Eliana too was aware of the wonders that awaited in Cusco. She knew I had been impressed by the large candles with thick wicks that illuminated our feasts at the Martinez compound and agreed to help me find some for my son Bruce. We secured a taxi and traveled across the city to a candle factory and found exactly what I wanted. |

When it did clear, I crossed the plaza and climbed up the steep, narrow street to two museums. The Incan museum had, among hundreds of artifacts, a large map showing the many pre-Incan civilizations. Some of the earliest flourished along the desert coastline, one of the world’s driest regions. To survive, these early peoples created ingenious irrigation systems, many of which were co-opted or copied by the Incas. Other cultures emerged along the shores of the giant Lake Titicaca, which someday I would like to see. Further up the hill, a museum of Pre-Columbian art had individual rooms for bronze, silver and gold artifacts, some so intricate it was hard to believe they were created thousands of years ago. |

|

|

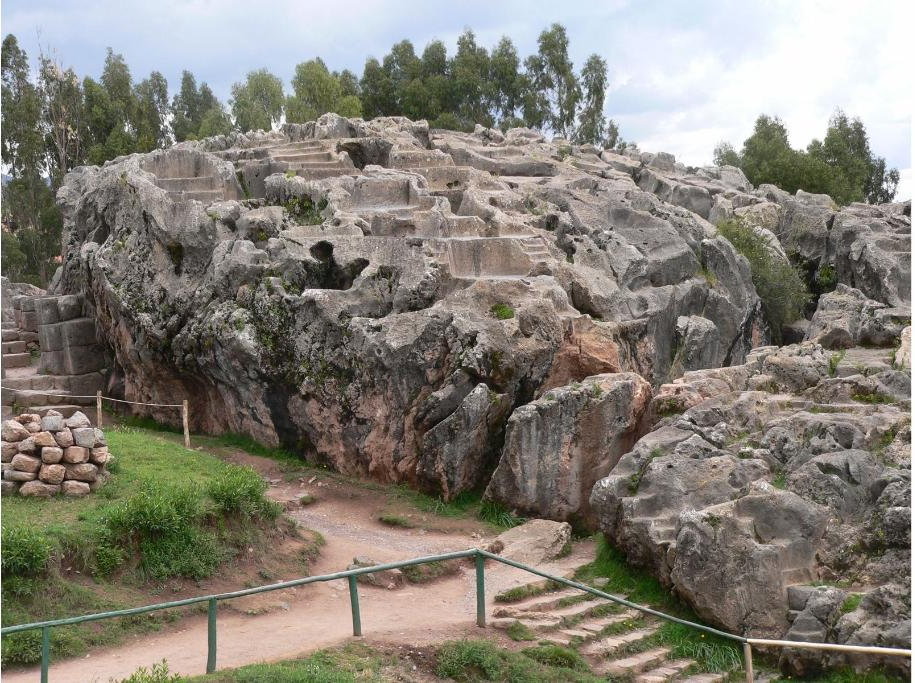

Sunday the 30th, Leon picked us up and we loaded ourselves into the van for the trip back to Yucay via a series of ruins. The Incas designed Cusco in the shape of a puma, the head of which was Sacsayhuaman. Either a fortress or a temple or both, Sacsayhuaman is comprised of massive blocks of stone, somehow hauled across the valley and assembled – permanently – above the city. Some blocks form sacred images and all border a flat field where, at the June Winter Solstice, great pageants are still performed. |

From there, we visited the pre-Inca Temple of the Moon, which looked like the moon and felt full of female power. We had a picnic there, abbreviated by the onset of rain. We actually passed another set ruins before stopping at the final archeological site of the day. Walking back (and up) from the road, we could see a series of pools, fed by channeled springs, which served as baths for sacred Inca virgins. The path followed a little stream bordered by wonderful old trees. The bark came off in strips that Viviana said she and her siblings used to use for paper. |

|

|

The rains returned and Leon was the personification of concentration as he maneuvered our van back ‘home.’ That night, Eliana gave a disquieting talk about some of the less glamorous aspects of Peru, including the fact that more than 25 percent of the poorer children are undernourished. |

The wedding was to be outside and chairs were arranged and flowers strewn. The guests were members of Viviana’s family (visiting from Cusco and Lima) and our group, by now almost family ourselves. We had to wait a while, in gentle sunshine, for the mayor to arrive. When he did, Avishai and Jason sat in two of the four chairs in front of the wooden table. We stood as Viviana and Marina entered from the main courtyard and sat in the other two chairs. Little Viviana carried the rings on a large white teddy bear. When the mayor finished the long civil ceremony and the papers were signed, the four rose to face the guests. They stood under a canopy created from the weaving Avishai had purchased from the train and suspended from four bamboo poles held by male relatives of the bride. Avishai and Viviana read their personal vows, translated by Eliana. Others came forward to state their best wishes. In addition to the two parents, one of our group had written a lovely poem, and Viviana’s Aunt Gloria expressed pure glee. |

|

|

We were all famished when we moved to another part of the yard for a feast that included lamb, chicken, potatoes, quinoa, vegetables, cheese, corn, and fruit salad, accompanied by wine, juice or chichu, a local beer made from corn. I sat at table with two of our group plus Gloria who encouraged me to load the chichu with sugar before drinking. |

Music sounded over loudspeakers and lured the guests from tables to lawn for dancing. Later, wedding cakes were shared. Marina had made with them with local grains and coca leaves then decorated both with flowers. The music and dancing resumed and threatened to last forever until, with Gloria’s encouragement, most of the guests departed and we gathered on blankets and small stools around Hector the Shaman. |

|

|

January 2 was our last day in Yucay. We packed up and returned to the Martinez complex for a final lunch and very difficult good-byes to our new family. Leon again arrived and loaded us back into the van for the drive to our Cusco hostel. There, after a group meeting, we scattered for various dinner destinations. With five others, I found a great pizza place on Avenue del Sol. The next morning we were to fly to Lima. |

| It is hard to summarize a journey that generated a better understanding of ancient civilizations and of a living people. As well as providing magnificent scenery, a new family and new friends. Plus cocoa parties and dancing, shamans, a wedding and a new poncho. Although I missed some sights because of illness or bad knees, I saw and did more than I had ever dreamed I’d do. And there was magic there. Not the stunning epiphanies I have had in other ancient lands – it was more subtle but just as real. By the end of this extraordinary tour, something in me had shifted. I have not taken anti-depressants since my return. |